Frannie Adams

"I love every inch of women’s bodies!

"I’ ve had a passion for photographing women since I was a teenager. My specialty is now intimate, erotic, close up photos - so close I can feel their body heat during a

shoot.

Because I am a woman, my models are more comfortable; whether one or two girls, or a boy and girl. I prefer shooting woman, but a boy in a girl’s mouth is very sexy! I also like self-portraits.

Can you guess which pictures are of me?

I hope you enjoy my galleries! The Books/DVDs page has information on my beautiful erotic books: Pussy Portraits and Pussy Portraits 2. Also my DVD: Pussy Portraits Video

#1.

If you’d like to see more of my erotic, close-up images of female body parts, please visit www.BodyParts.biz. We post new content daily.

If you send me an email, I’ll notify you of my new erotic DVD and Book releases.

Ciao!

Frannie"

http://www.frannieadams.com

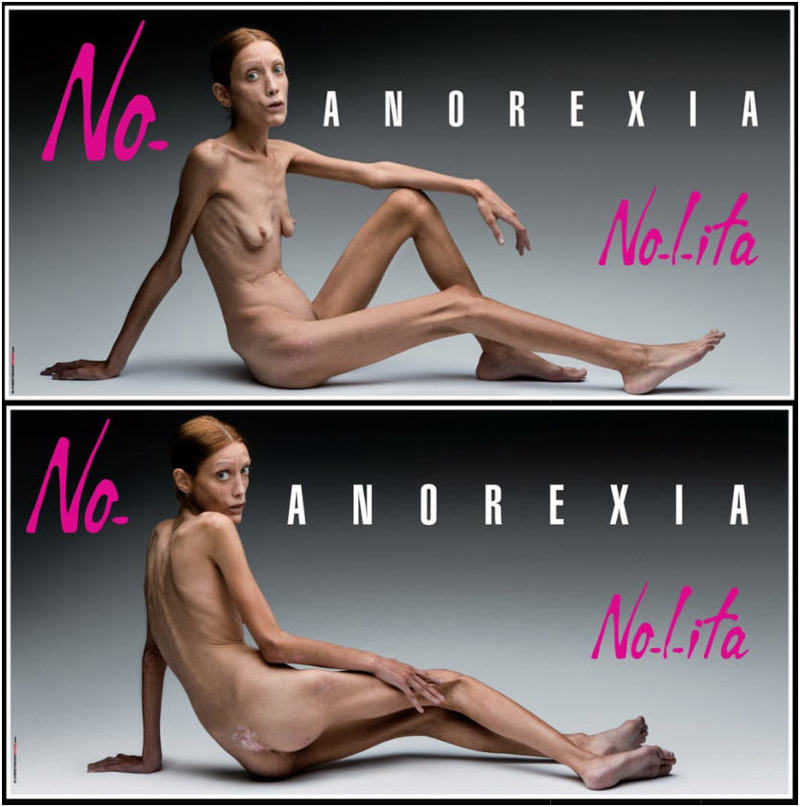

Mort d'Isabelle Caro

"La comédienne et mannequin française Isabelle Caro est décédée le 17 novembre dernier à l'âge de 28 ans, a révélé mercredi le site suisse de 20 Minutes. Une mort, dont les causes ne sont pas connues et qui avait été gardée secrète par la volonté de ses proches.

La jeune femme était devenue une figure de proue de la lutte contre l'anorexie, maladie dont elle souffrait depuis l'âge de 13 ans, en posant nue devant l'objectif du photographe Oliviero Toscani pour une campagne italienne «No Anorexia». Elle pesait alors 31 kg pour 1 m 64. Un véritable choc.

L'image de son corps décharné a eu le mérite de marquer les esprits et de lui permettre d'évoquer cette maladie dans les médias du monde entier. «Le but c'est de choquer pour sensibiliser», indiquait-elle alors pour expliquer pourquoi elle avait accepté de poser pour le photographe Italien, habitué aux photos controversées avec ses campagnes pour la marque Benetton. «J'ai accepté pour alerter les jeunes filles en leur montrant les dangers des régimes, des diktats de la mode et des ravages de l'anorexie».

«La petite fille qui ne voulait pas grossir»

Cette image a été comme un électrochoc pour la jeune femme elle-même. « Depuis la photo, j'ai pris 3 kg. Je suis en meilleure santé et j'ai envie de me battre», nous déclarait-elle quelques mois après la campagne. Elle avait témoigné dans «La petite fille qui ne voulait pas grossir», un ouvrage poignant sorti en mai 2008. Isabelle Caro luttait toujours énergiquement contre sa maladie et avait annoncé en mars 2010 avoir atteint le poids de 42 kg, une victoire pour celle qui tombait dans le coma cinq ans auparavant, ne pesant alors que 25 kg.

La jeune femme d'origine marseillaise est partie dans la plus grande discrétion. C'est sur la page Facebook que l'une de ses amies publiera finalement un mot annonçant son décès. «Elle avait été hospitalisée pendant 15 jours pour une pneumopathie et dernièrement elle était très fatiguée, mais je ne connais pas la cause de son décès», a déclaré au site 20min.ch son ami, le chanteur Vincent Bigler".

http://www.leparisien.fr/actualites-informations-direct-videos-parisien

Corps en image

17 décembre 2010

Daniel Siret du CERMA/Nantes nous signale ce colloque

Organisateurs : Evelyne Barbin et Dominique Le Nen / Centre François Viète – Université de Nantes ;

Amphithéâtre du Museum d’histoire naturelle

T hèmes : Corps anatomiques / Corps et arts visuels / Corps célestes / Corps physiques

Programme :

Vendredi 21 janvier 2011

« Le maniérisme : un art de la crise et de l’invenzione au XVIe siècle en Italie » /Catherine Boyer Le Treut (Musée des Beaux-Arts, Nantes)

« Dissections et images du cerveau chez Vésale » /Jacqueline Vons et Stéphane Velut (CESR et Faculté de médecine, Université de Tours)« Des moyens concrets au service du sensible, la

représentation du corps dans une pratique contemporaine de la peinture » / Hubert de Chalvron (École supérieure d’arts de Brest)

« De la transgression à la transparence : évolution de l’image du corps ». / Dominique Le Nen (CFV Nantes et CHU Brest)

« L’art biotechnologique : un cabinet de corps fantômes »/ Catherine Voison (Paris I et laboratoire LETA)

« Les mains dans la peinture du Caravage » / Fabrice Rabarin (Angers)

« Le corps en cire, objet d’art ou objet pédagogique »/ Michel Rongières (CHU PURPAN, Toulouse)

« La mélancolie dans l’Art »./ Alain Fabre (Saintes)

Samedi 22 janvier

« La représentation du corps dans la cinétographie de Rudolf Laban »/ Evelyne Barbin (CFV, Nantes)

« L’oeil, au carrefour de la pratique scientifique et de l’image »/ Florence Riou (CFV, Nantes)

« La résection du poignet vue par Clémot, chirurgien de la marine sous le Premier Empire »/ Philippe Liverneaux (CHRU Strasbourg).

« Les infrastructures portuaires dans l’Ouest de la France entre représentations graphiques et représentations figurées (XIXe s – début XXe.s) »/ Françoise Sioc’han (CFV, Nantes)

« La matière vue comme un corps vivant dans l’imagerie alchimique »/ Antony Vinciguerra (CRHIA, Nantes)

« Images de l’invisible. Corps et rayons X dans La Nature (1896 – 1914) »/ Manuel Chemineau, (Universitât Wien) et Sylvain Laubé (PaHST, Brest).

« Un poète sous influences ? Paul Valéry, l’image du corps entre arts et sciences » / Stéphane Le Gars (CFV, Nantes)

« Blocs erratiques et transformation de la peinture glaciaire occidentale des années 1770 à 1850 »/ Alexis Drahos (Université Paris IV

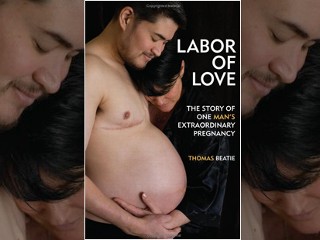

Thomas Beatie

éThomas Beatie (né en 1974), est un Américain devenu légalement homme[1] (archive perdue), connu et reconnu dans les médias pour avoir été enceint[2],[3].

Thomas Beatie était de sexe féminin à la naissance, mais transgenre FtM (Female To Male), il est devenu officiellement un homme suite à une intervention chirurgicale (réduction mammaire) et des injections de testostérone.

Marié depuis 10 ans avec une femme stérile, il a bénéficié d'une insémination artificielle afin de concevoir l'enfant du couple. Une grossesse a été rendue possible par le fait que Beatie avait conservé ses organes sexuels internes et externes féminins. Après avoir arrêté son traitement hormonal, l'insémination artificielle a pu avoir lieu avec succès. Une césarienne était prévue initialement[4]. L'accouchement par voie naturelle a eu lieu le 29 juin 2008 au matin[5]. L’enfant est une fille prénommée Susan. Le 9 juin 2009, il a donné naissance à un deuxième enfant, un garçon. Ils attendent leur 3e enfant pour 2010"

http://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Thomas_Beatie

.

Read an Excerpt of Thomas Beatie's New Book

“Labor of Love” by Thomas Beatie

c.2008, Seal Press $24.95 / $32.50 Canada 280 pages

I have been a daughter and a son, a sister and a brother, a boyfriend and a girlfriend, a beauty queen and a stepfather, a girl scout and a groom. But today I am just an ordinary human being in a whole lot of pain.

Today, it is happening—it is finally happening. I am wearing an enormous, 4x white T-shirt, on inside out. The soothing, insistent sound of a heartbeat—around 140 of them each minute—is the only music in my otherwise quiet birthing room. My contractions are intensifying, and every couple of minutes I feel this surging pain that starts from inside my gut and radiates out. I remember trying to do a dismount from a chin-up bar when I was ten, and landing square on my back. That was the worst pain I ever felt, but this is way, way worse. Our midwife puts a cold washcloth on my forehead; my wife Nancy kisses me tenderly on my cheek.

It has been a long, hard, often surreal journey to get this point, and now I have to summon one last big burst of energy for the final leg. "Gravity is your friend," says the midwife, by way of urging me to walk around to try to speed things along. But the truth, I am finding, is that having a child is not in any way a passive act. You don't just show up and wait for the baby to arrive. You have to will the baby out of your body, and that means marshalling every last ounce of strength and resolve that you have.

Nancy puts her hand on my belly and feels our daughter thrashing around, and she tells me, "Don't worry, she'll be here soon." But the hours pass. I focus on odd little details to take my mind off the pain. Our midwife's left index finger is wrapped entirely in surgical tape; she cut it slicing whole grain bread that morning. This strikes me as neither a good nor bad omen, just unlucky for her. I also notice she has a tiny diamond stud in her left nostril. You can barely make it out in the dimly lit room but when she leans in to fix my blanket or move me from side to side, it sparkles. She's a wonderful woman, so calm and reassuring, and I like that she's obviously a bit of a hippie, too.

I am 100 percent effaced; I am also nearly fully dilated at 9 centimeters. And still no baby. We got to the hospital in the early morning; it's nearly nighttime now. "Let us know when you feel the urge to push," says our midwife. "Not just pressure, but a real urge to push." Nancy starts watching out for what she calls my "pushy face," then asks if she can get her own epidural. That's Nancy; cracking jokes, making everyone feel at ease, and still remaining a tower of strength for me to lean on. That morning at home she sifted through a bowl of jellybeans and brought all the purple and orange ones—my favorites—to the hospital. She slips a couple of them to me—a simple, throw-away gesture between a husband and a wife—but it strikes me yet again, as it does every day, that I could never, ever have done this without her right by my side. Nancy gets up to straighten my sheets and touches my face with her hand. She says, "You're nose is really cold, like a puppy."

A nurse gradually fills my IV with pitocin, which is supposed to increase contractions and speed along my labor. "Your uterus is really tired," the midwife tells me, and I think, "That makes two of us." We're going on twelve hours now, but the nurse assures us, "That's the average length of labor for a first-time mother." Nancy gently corrects her by asking, "What about for a first-time father?"

A little earlier, our midwife brought over a red velvet sack filled with little slate tiles, each shaped like a heart and bearing a single word. "Pick one out and that will be your focus word," she says. Now I reach in, pull out a pink heart and show it to everyone. "Serenity!" says the midwife. But in fact, it's misspelled on the tile as "Sereinty." How perfect, I think—even my focus word is mixed-up, nonsensical, a deviation from what is known and expected. That has been the story of my entire pregnancy—no one has known quite what to make of it, or been able to truly understand what it means. To me, it couldn't be simpler. I am a person who is deeply in love and wants to have a child. But, just like my jumbled focus word, what I know it to mean and what the world reads it as, are two very different things.

"Remember, Thomas, sereinty," Nancy tells me later. "Try to be sereine."

Things suddenly get serious; a doctor is hustled into the room. It is time for my baby to be born. "Let's get busy and push," the midwife says, and I push harder than I ever thought I could. The pain is searing, and I think I might pass out. But I keep pushing. I hold tight to Nancy's hand, and every once in a while I steal a look at my white, laminated hospital wristband. Just like my wife's hand, it's a source of strength for me. There's nothing all that unusual about it, unless you know my whole story. But a single thing on that band—a single, solitary lettervis, for me, a symbol of the most emotional and triumphant battle of my life. On the band, in simple type, it reads":

Erika Lust

www.erikalust.com

"Son premier projet, le court-métrage intitulé “The Good Girl”, qu’elle dirige et écrit, est tourné en 2004, peu de temps après la fondation de sa propre entreprise Lust Films. Ce court-métrage fera plus tard partie du film Five Hot Stories For Her, composé de cinq courts-métrages pornographiques, et récompensé à l’occasion de plusieurs remises de prix internationales, pour “meilleur scénario” au Festival International du Film Érotique en 2007 à Barcelone (FICEB Award), “meilleur film de l’année” par le Feminist Porn Awards de Toronto en 2008 et également récompensé aux Venus-Eroticline-Award en 2007 à Berlin. Five Hot Stories For Her reçoit les honneurs au CineKink Festival de New York (2008) et la même année, Erika Lust tournera le documentaire expérimental “Barcelona Sex Project” qui sera recompensé au Venus Festival de Berlin, projeté au CineKink de New York et au X-Rated d’Amsterdam l’année suivante. Son dernier film, Life Love Lust, sort en 2010. Erika Lust réalisera aussi deux autres courts-métrages, “Handcuffs” en 2009 qui recevra à son tour de nombreuses récompenses et “Love me like you hate me” en 2010 qui inspirera l’écriture du livre éponyme en collaboration avec Venus O’Hara. Ces deux créations tournent autour des thèmes du fétish et du BDSM.

Son livre “Good Porn” est publié en 2009 par Seal Press."

http://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Erika_Lust[

Documental erótico, íntimo e independiente.

Dirigida por: Erika Lust

Protagonizada por:

LAS CHICAS Dunia Montenegro, Irina Vega y Silvia Rubí

LOS CHICOS David Galant, Joni Lapaz y Joel Acosta

Sex Project es un documental erótico, íntimo e independiente, donde nos adentramos en la vida de tres hombres y tres mujeres para conocerles en profundidad, incluidos sus orgasmos reales. Ellos y ellas comparten con nosotros sus pensamientos, pasiones y reflexiones en una entrevista en profundidad, también llevándose una cámara a su vida de cada día para retratarla con naturalidad y finalmente invitándonos a asomarnos a su placer más privado e íntimo.

Seis retratos íntimos, seis entrevistas personales y seis orgasmos reales.

Género: Documental.

Formato: DVD.

Duración: 100 min.

Idioma: Castellano

Subtítulos: Castellano, Inglés, Alemán, Francés

Sistema: PAL DVD

DVD EXTRAS

Making of y Entrevista con Erika Lust

Trailers y Teasers

Trailer de Cinco Historias para Ellas

Genre, sexualité et réflexivité. Sex and fieldwork

La dimension sexuée du processus d'enquête (2010-2011)

Sex and fieldwork

Publié le mardi 02 novembre 2010 par Marie Pellen

Les recherches en sciences sociales sont encore trop souvent aveugles à la dimension sexuée du processus d’enquête. Les analyses réflexives se sont multipliées depuis une trentaine d’années, mais elles continuent de minimiser – voire d’éclipser – les interrogations posées par le sexe des chercheur-e-s et les enjeux particuliers qu’il soulève. Et si ces questionnements sont aujourd’hui discutés par les sciences sociales anglo-saxonnes, ils peinent à s’exporter et résonner dans l’espace français. À partir d’études de cas, ce nouveau séminaire vise ainsi à développer une réflexion interdisciplinaire sur la place du genre et de la sexualité dans le processus de recherche (anthropologie, histoire, géographie, sociologie). Seront notamment abordés : l’influence du sexe dans les interactions entre chercheur-e-s et enquêté-e-s, les problèmes éthiques et déontologiques posés par l’analyse des questions sexuelles et la tension entre explicitation et préservation de l’intimité du choix du sujet à sa restitution. Si les travaux centrés sur le genre et la sexualité seront particulièrement discutés, le séminaire sera ouvert à une pluralité d’objets, ces interrogations traversant tous les domaines des sciences sociales.

Séminaire de recherche (EHESS)

1er mercredi du mois de 19 h à 21 h (salle 1, 105 bd Raspail 75006 Paris), du 4 novembre 2009 au 2 juin 2010

Les recherches en sciences sociales sont encore trop souvent aveugles à la dimension sexuée du processus d’enquête. Les analyses réflexives se sont multipliées depuis une trentaine d’années, mais elles continuent de minimiser – voire d’éclipser – les interrogations posées par le sexe des chercheur-e-s et les enjeux particuliers qu’il soulève. Et si ces questionnements sont aujourd’hui discutés par les sciences sociales anglo-saxonnes, ils peinent à s’exporter et résonner dans l’espace français. À partir d’études de cas, ce nouveau séminaire vise ainsi à développer une réflexion interdisciplinaire sur la place du genre et de la sexualité dans le processus de recherche (anthropologie, histoire, géographie, sociologie). Seront notamment abordés : l’influence du sexe dans les interactions entre chercheur-e-s et enquêté-e-s, les problèmes éthiques et déontologiques posés par l’analyse des questions sexuelles et la tension entre explicitation et préservation de l’intimité du choix du sujet à sa restitution. Si les travaux centrés sur le genre et la sexualité seront particulièrement discutés, le séminaire sera ouvert à une pluralité d’objets, ces interrogations traversant tous les domaines des sciences sociales.

1er séance : 3 novembre 2010

Marianne Blidon, Maître de conférences à l’Université Paris 1/Panthéon-Sorbonne, IDUP

Sébastien Roux, Postdoctorant à l’EHESS, Iris

2e séance : 1er décembre 2010

Thomas Fouquet, Doctorant à l’EHESS, Iris

3e séance : 5 janvier 2011

Anne Volvey, Maître de conférences en géographie à l’Université d’Artois, UMR Géographie-Cités.

4e séance : 2 février 2011

Marwan Mohammed, Chargé de recherche au CNRS, CMH

5e séance : 2 mars 2011

Yannick Fer, Chargé de recherche au CNRS, GSRL

Gwendoline Malogne-Fer, Postdoctorante, rattachée au GSRL.

6e séance : 6 avril 2011

François Gaspard, Maître de conférences en sociologie à l’EHESS, ancien membre du CEDAW

7e séance : 4 mai 2011

En attente de confirmation

8e séance : 1er juin 2011

Discussion et présentation de travaux d’étudiants

- genre, sexualité, réflexivité, enquête, terrain

- Paris (75006) (105 bd Raspail (EHESS, salle 1))

- mercredi 03 novembre 2010

- mercredi 01 décembre 2010

- mercredi 05 janvier 2011

- mercredi 02 février 2011

- mercredi 02 mars 2011

- mercredi 06 avril 2011

- mercredi 04 mai 2011

- mercredi 01 juin 2011

- Marianne Blidon

courriel : marianne [point] blidon (at) univ-paris1 [point] fr - Sébastien Roux

courriel : sebastien [point] roux (at) ens [point] fr

- Marianne Blidon

courriel : marianne [point] blidon (at) univ-paris1 [point] fr

« La dimension sexuée du processus d'enquête (2010-2011) », Séminaire, Calenda, publié le mardi 02 novembre 2010, http://calenda.revues.org/nouvelle17873.html

Variations sur le corps

variations sur le corps organisée par Yves Coppens et Michel Serres .....

Avec Philippe Barbarin, cardinal-archevêque de Lyon - Delphine Censier, photographe - Daniel Herrero, ancien joueur de rugby - Frederic Kaplan,chercheur en intelligence artificielle - Brigitte Lahaie, animatrice radio - Alexis Laurent, chirurgien - David le Breton, anthropologue et sociologue - Maguy Marin, danseuse et chorégraphe - Isabelle Queval, philosophe - Angela Sirigu, directrice de recherche au CNRS, neuropsychologue - Hans Silvester, photographe - Georges Vigarello, philosophe.

http://entretiensdelacite.docforum-lyon.com/

Sur les métamorphoses de l’hominisation. De l’état de quadrupède à l’homme debout (homo erectus), le corps en se relevant rencontre les sens et les fédère pour les unifier en lui

Sur la puissance physique que le corps (mis par nature à la place du plus faible parmi les vivants), peut développer lorsqu’il est soumis à l’entraînement exigeant du sportif : son endurance, sa capacité à négocier avec la souffrance et à surmonter la douleur, les prouesses de l’équilibre instable en portent témoignage.

Sur le vertige avec le mystère de l’incarnation, le fils de dieu et de l’homme s’incarne dans le sein d’une femme et laisse en mémoire notre corps et son sang, encore le vertige avec l’émerveillement de la transsubstantiation quand nous devons apprendre ou réapprendre de nouveaux enchaînements gestuels.

Sur la connaissance, Buffon, dans son « Histoire naturelle de l’homme (1749) », Condillac dans son « Traité des sensations (1754) », Michel Serres dans « Les cinq sens (1985) », montrent comment les sens sont à l’origine d’un savoir que la science canonise.

« Eurêka !j’ai trouvé la force verticale qui lève le corps… Le corps oui, le corps encore. Nu. Parmi le tournis et le vertige, nous ne trouvons rien que nu. Soulevés de joie ! »

Ecologie corporelle

L'écologie corporelle

L'écologie corporelle

vers une cosmotique

Bernard Andrieu

Éd Atlantica, 2011

Coffret de 4 volumes - Tome 1 :

En plein soleil - Vers l'énergie - Tome 2 : Prendre l'air - Vers l'écologie corporelle -

Tome 3 : Bien dans l'eau - Vers l'immersion - Tome 4 :

Un goût de terre - Vers la cosmosentation - A paraitre début 2011

Faute de connaître l'écologie de notre propre corps, nous recherchons dans la nature une harmonie qui se trouve à l'intérieur de nous : notre microcosme ne correspond plus avec le macrocosme. Nous cherchons à la montagne, sur les plages ou à la campagne des paysages sans correspondance entre notre corps et la nature. Les parfums, les couleurs et les sons, des Correspondances des Fleurs du Mal de Baudelaire, ne se répondent plus.

Pour Empedocle : c'est par la terre (qui est en nous) que nous connaissons la terre, par l'eau que nous connaissons l'eau, par l'éther, l'éther divin, par le feu, le feu destructeur.

Les découvertes de l'atome, du neurone, du gène ou des cellules souches ont développé une indépendance des sciences de toutes

références cosmogoniques : l'hygiène, la prévention, l'exploitation des ressources nous procurent une domination aseptisée de la nature sans contact direct avec les éléments .

Se déplacer à pied, prendre l'air, transformer l'énergie solaire, s'enfoncer dans la terre, se trouver bien dans l'eau, prendre le gout de terre de produits sont autant de modes d'écologiser son corps au quotidien. Si le corps éprouve en lui l'effet des éléments sans les subir, l'interaction avec la nature ne pourra plus nous isoler de la nécessaire restauration écologique de l'environnement.

Aucune conférence mondiale ne remplacera la conscience corporelle de notre interaction avec les éléments, pour autant que l'éducation écologique pourrait être réflexive et sensorielle et pas seulement morale et prescriptive. Sans une intériorisation des techniques écologisant les corps, chacun(e) peut croire que les éléments sont extérieurs et maîtrisables : nous sommes pourtant dans le flux, dans le courant d'air, dans le tremblement de terre et dans les voies d'eau.

Avec l'écologie corporelle, la cosmotique ne se tient pas ni à distance ni en idolâtrie des éléments naturels : la nature n'est ni bonne ni mauvaise, mais elle questionne sans relâche nos interactions physiques avec elle par les limites mêmes de notre corps et l'inventivité verte de nos techniques.

Bernard Andrieu est philosophe du corps et professeur en épistémologie du corps et des pratiques corporelles à la faculté du sport de Nancy, et au sein de Acccorps & LHSP UMR 7117 CNRS. Il a publié de nombreux ouvrages sur le corps dont : Le dictionnaire du corps, éd. CNRS 2006 ; Toucher, se soigner par le corps, éd. Belles Lettres, 2008 ; Devenir hybride, éd PUF Nancy 2008 ; Le monde corporel, éd l'âge d'homme, 2009. Il co-anime la revue interdisciplinaire Corps, éd. CNRS.

DIETS & FOOD PATTERNS

FOURTH INTERNATIONAL SYMPOSIUM OF CORPUS

DIETS & FOOD PATTERNS

Myths, Realities and Hopes

Tbilisi, July 5th-6th 2011

CORPUS

INTERNATIONAL GROUP FOR THE CULTURAL STUDIES OF THE BODY

&

ILIA STATE UNIVERSITY

STOCKHOLM UNIVERSITY

CALL FOR PAPERS

Founded in 2009 after a series of seminars organised between 2001 and 2008 at the EHESS

(Paris) and the Autonomous University of Madrid, CORPUS aims to be an effective

participant in the construction of a widely diverse and scientifically based dialogue on the

subject of the anthropological aspects of the body. CORPUS aims to offer a forum of crossthinking

and open dialogues about this fascinating subject.

CORPUS now boasts around three hundred fifty researchers from more than sixty different

countries. The themes of the preceding symposia were "The Beautiful and the Ugly: Body

Representations" (Lisboa, January 2010), "Foreign Bodies: Enhancing & Invading the Human

Body" (Moscow, May 2010) and "Bodies & Folklore(s): Legacies, Constructions and

Performances" (Lima, October 2010) The fourth International Symposium of CORPUS is

organised with the support of the Ilia State University (Georgia) and the University of

Stockholm (Sweden). Its theme will be "Diets and Food Patterns: Myths, Realities and

Hopes".

As Audrey I. Richards wrote more than seventy five years ago, "Nutrition as a biological

process is more fundamental than sex. In the life of the individual organism it is the more

primary and recurrent physical want, while in the wider sphere of human society it

determines, more largely than any other physiological function, the nature of social grouping,

and the form their activities take". A human body is by essence an eater body that is in a

precise cultural context and that needs to be satisfied foods and not nutriments – to use a

famous Jean Tremolières's formula. Consequently, all civilisations developed knowledge

about the incorporation of food by the body. Of course, these cultural productions around a

biological necessity were generally linked with largest thoughts about the human nature, the

world, the universe, the divinity. The basis of the dietetical systems can change, as their

internal logics from a period to another, from a region to another or from a social group to

another. Today, the Omega 3 and the Vitamin C are not the same things for the physicians or

for your average bloke who consumes them under the form of miraculous dietary

supplements. The currently fashionable ideal "traditional diets" remember that the dietetical

models can be subtle constructions and good commercial products. But, they are also an

invitation to observe and think about the everyday food practices and their consequences on

the body avoiding excessive simplifications.

We invite researchers interested in the bio-cultural approach of human nutrition

(archaeologists, anthropologists, historians, physicians, psychologists, sociologists, etc.) to

participate in this meeting, especially considering one of the following themes:

• Dietetical discourses and medical considerations about food: logics and evolutions of the

dietetical systems; turning points in academic medical discourses about food / substitution

of dietetical systems, relations between academic and popular dietetic knowledges.

• Ideal "traditional diets" (Cretan diet, etc.): construction, promotion, influences on high

cuisine/everyday cuisine, etc.

• Dietetics, nutrition sciences and ideologies: philosophical thoughts about food

consumption, dieticians' visions of the society.

• Medicine-foods; dietary supplements, "healthier substitutes" and "detrimental foods":

fashions, markets, contexts of consumption, dynamics of depreciative discourses, etc.

• Eating to build oneself: dietetical sub-cultures (body builders, militant vegans, etc.),

particular relationships with food (anorexia, bulimia, orthorexia, etc.).

• Consequences on the body of concrete food practices: nutritional deficiencies and their

cultural representations, social valorisation/depreciation of the fat body, etc.

• Eating in another world: dietetics and food practices in Science Fiction, popular tales, etc.

Presentations will be 20 minutes long and must be delivered in English. The proposals must

include an abstract (150-300 words) and a current CV. The deadline for receiving presentation

proposals is March 15th 2011. Please use the address provided below to send your proposal

to Frédéric Duhart, Paata Donandze, Ulrica Söderlind, F. Xavier Medina and Mohey Mowafy.

All proposals will be evaluated by an international scientific committee. The symposium will

be held July 5th-6th 2011 at the Ilia State University, Kakutsa Cholokashvili Ave 3/5, Tbilisi.

Transportation, visa, travel insurance costs and accommodation will be the sole responsibility

of each participant.

Contacts:

Frédéric Duhart

CORPUS General Coordinator

frederic.duhart@wanadoo.fr

Paata Donandze

4th Symposium Coordinator

paata_donadze@iliauni.edu.ge

Scientific Commission Coordinators

Ulrica Söderlind

(Archeology, history)

ulrica.soderlind@ekohist.su.se

F. Xavier Medina

(Anthropology)

fxmedina@gmail.com

Mohey Mowafy

(Nutrition)

mmowafy@nmu.edu

More information about CORPUS and its activities: http://corpus.comlu.com